Constructing Relationships

June brought the annual London Festival of Architecture, bringing together thousands of people to meet, discuss, contemplate and enjoy architecture, and the them of this year, In Common.

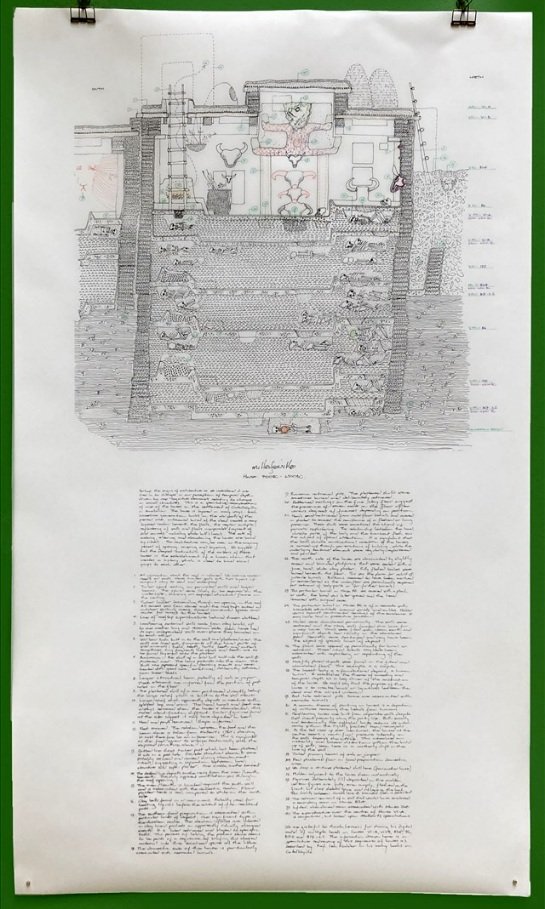

As part of this, I attended an afternoon of Architecture related talks and later a party at the Royal Academy. Mid way through the afternoon, Níall McLaughlin spoke about his processes and piece in the show, Millefeuille. The work has many layers of reference (the title translating to ‘a thousand leaves’), and it was compelling listening alongside the piece.

The talk particularly resonated with me, when at one point McLaughlin was discussing construction as being only a negative experience for Architects. That is insofar as the thousands of hours spent on hundreds of drawings, all meticulously detailed and co-ordinated, when they materialise on site, an element of improvisation and chaos usually ensues due to one reason or another.

All the years of knowledge, the planning, collaboration, long days perfecting the design and co-ordinating all aspects cannot account for life, and someone else translating these drawings and placing their own emphasis and mark on them. And any changes manifested from the original intent are seldom master strokes of design and aesthetics, prompting the Architect to wish that they too had not thought to misalign the lights or change the nosing detail of the stairs to a simpler one to construct.

McLaughlin also went on to discuss the nature of the home and community historically, and the how projects such as helping rebuild a wall or re-roofing a house would, in the not too distant past be collective acts. These acts of collaboration would, as well as strengthening the physical properties of a building, strengthen and solidify relationships. This in turn would increase an individuals sense of wellbeing, accomplishment and place in society.

It occurred to me that like communities, Architects also were traditionally more hands on during the construction process than we are now, with, in my experience, large proportions of office workers making infrequent, at best, trips to site during construction. This has been exacerbated by D&B contracts, and the Architects relegation to draftsperson, as the main contractor takes on the sceptre of decision maker and constructor. This has led to (some) removal of risk, but also a removal of agency and latterly, finances away from the Architect. But I believe that it has also been responsible for more than that. Removing the Architect as main decision maker has, in turn, removed their involvement in the process of construction, and to a degree, from the construction site, as their need there is diminished, and is now left to field RFI’s etc.

As some businesses and practices have been keen to point out, being more insular and living a life without much human interaction, and staring at a computer screen all day isn’t the best thing for our mental or physical health. But for many practices, working in the office can be similarly solitary, with the added joys and costs of commuting. Doing drawings, revisions, answering queries and sending emails are all necessities. But if they make up the vast majority of the experience of a practice or office, there will be an inevitable decline in morale, productivity and satisfaction, and ultimately lack of quality staff retention.

Of the many practices I’ve worked at, one that I enjoyed more than others was Pollard Thomas Edwards. It is a medium-large practice, but held events to engage the staff. Annual trips were taken abroad. Weekly crits were held in the basement, so teams could get feedback from their echo chamber, and younger members could hear and learn what projects are going on, and how they are being developed and why decisions are made. Weekly lunches were cooked for the entire office by a rota of the whole office. And the project I was on, despite being a Part II, I felt impactful, integral and like my opinions were valid and valued, and were making a difference to the end product; and thus, people’s lives in the long term. It can’t be overstated how much these things affect staff morale and are an investment in the practice and the future.

As a qualified, but no longer practicing Architect, I’ve heard first, and second hand from friends or colleagues of many young Architects, disillusioned with the industry (including a handful of people on the LFA photo walk that I led). We are brought in with aspirations of helping design the world around us, changing things for the better, and expressing the creativity we possess and are encouraged to explore during the gruelling university process. When the reality of the detached life of practice sets in, and endless drawings, schedules, variations, co-ordination and emails sets in, the grand visions previously held begin to crumble.

Maybe this has always been the case, and this is no different to 20, 30, 50 years ago!? Maybe it’s just the human condition and modern approach to want to try several different passions over a lifetime rather than train in one discipline and stay in that career until retirement. But maybe it’s a sign to incorporate a more hands on approach at all levels of practices, to build the feeling of satisfaction, roundedness, new experiences and community that we used to experience in a simpler time.

At a time when architecture and the construction industry is struggling and sputtering, people need nurturing and valuing, and practices need to move forward together as a progressive community, involving staff with a multitude of tasks and experiences to enrich the practice, Architects, and the wider society.